China’s high-stakes plan for self-transformation into a high-tech superpower is encapsulated in its “Made in China 2025” initiative.

In May 2015, China’s State Council officially announced Made in China 2025 (“MIC 2025”), which calls for a mix of market initiatives, technical innovation and state intervention to incentivise and drive the accelerated development of 10 key industrial sectors:

- Next-generation information technology (IT)

- Automated machine tools & robotics

- Aerospace and aeronautical equipment

- Maritime engineering equipment and the manufacture of high-tech shipping

- Advanced rail equipment

- New-energy vehicles and equipment

- Electrical power-supply equipment

- New materials

- Biomedicine and high-performance medical devices

- Agricultural machinery and equipment

These industries constitute nearly 40% of China’s entire value-added manufacturing.

The guiding principles of MIC 2025 are innovation in manufacturing; quality over quantity; green development; optimising the growth of China’s indigenous ‘homegrown’ industry; and nurturing human talent.

The goal is to comprehensively upgrade the ten select industrial sectors, making them ultra-automated and efficient, along the lines of the German concept of Industry 4.0, allowing them to compete internationally.

The plan’s very ambitious goals are raising the domestic content of core components and materials to 40% by 2020 and 70% by 2025. Imports of foreign-made components and products will be proportionally reduced. To that extent, MIC 2025 is a long-term effort to promote productive self-reliance.

When the chips are down

Nevertheless, MIC 2025 immediately exposes China’s “Achilles’ Heel”, its reliance on foreign-produced semiconductor chips, with the import overhang reportedly at around 80-90%. If the select ten sectors are to be ultra-automated, with processes constantly optimised via big data and data analytics, in at least close to real time, then the success or failure of MIC 2025 really hangs on the super-fast development of a domestic chip industry.

Trying a new approach, China had signalled a new round of major investment in a domestic chip industry with the 2014 IC Plan, announced in June 2014 by the China State Council.

The IC Plan, among other forms of support, proposes investment of some US$160 billion, over 10 years, to develop a domestic chip industry, including, where possible via M&A. Not surprisingly, the proposed schedule more or less parallels that of MIC 2025.

In practice, achieving an indigenous semiconductor industry will be an enormously difficult undertaking for China, especially if it is to be truly globally competitive. To be globally competitive, China will require process technology on a par with that of players such as Samsung, TSMC, Intel and GlobalFoundries – tough company to keep.

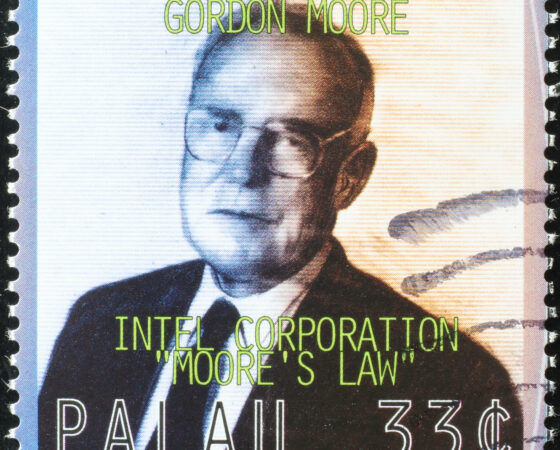

This is in a situation where “keeping up with Moore’s Law” is no longer an automatic swing of the production pendulum, and where capital equipment is vastly expensive, and, realistically for China, only available on an import basis. A new state-of-the art fab now costs US$5 billion and counting. And once built, it requires veteran expertise in chip fabrication – a complex set of processes rather than straightforward ‘conveyor belt’ factory production.

To date, China’s strategy has been to attract foreign investment by the likes of Samsung, TI, Taiwan’s TSMC and UMC, Intel and SK Hynix, all of whom have built fabs in China, with presumably some degree of technology transfer forming part of the agreements. While, MIC 2025 seeks to slow and limit reliance on foreign expertise, in the field of semiconductors and chip fabrication it’s likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

No magic bullet?

While MIC 2025 is hugely bold and ambitious, it seems realistic to expect that, in fact, China will need to rely on imported technology, certainly in semiconductor design and fabrication, for many years to come. That’s where expertise in supply and distribution, including practical logistics within an extremely large and diverse country, will continue to be required and relied upon. That’s where the ability of foreign investors to work with their Chinese partners and customers, in the development of unique solutions, will continue to be a winning formula.